Blog

Explained: Why Insurance Covers Opioids vs Non-Pharmaceutical Options - A. Baxter MD

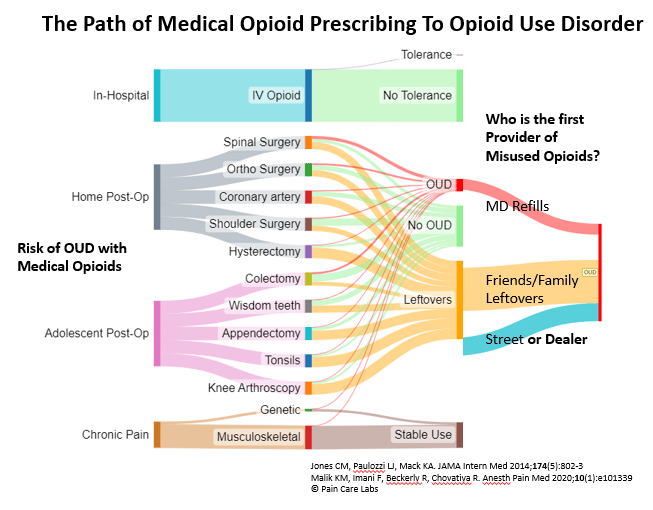

Pain is the primary reason people seek medical care. Pain is also the problem that ignited the opioid crisis and continues to supply fuel. Eighty percent of opioid misuse begins with a pill prescribed for pain.

Purdue invested heavily in marketing Oxycontin to physicians, training them that home opioids are the standard of care for recovery from surgery. While addiction debunked the myth of universal safety, two fallacies embedded in the Sackler marketing campaign persist in American culture: we still believe pain-free is the goal, with pills as the path. New neuroscience contradicts both. Nonetheless, opioids at discharge remain reimbursed, while proven FDA-cleared drug-free alternatives are not. The Purdue fallacies and explicit Medicare policy are blocking patients from effective pain relief.

Before the true risks were known, home prescriptions for 90 narcotic pills were not uncommon. This practice left a legacy of leftover medicine-cabinet pills to fuel inappropriate use. While still over-prescribed, the opioid crisis (and DEA requirements) have re-educated MDs, reducing circulating opioids.

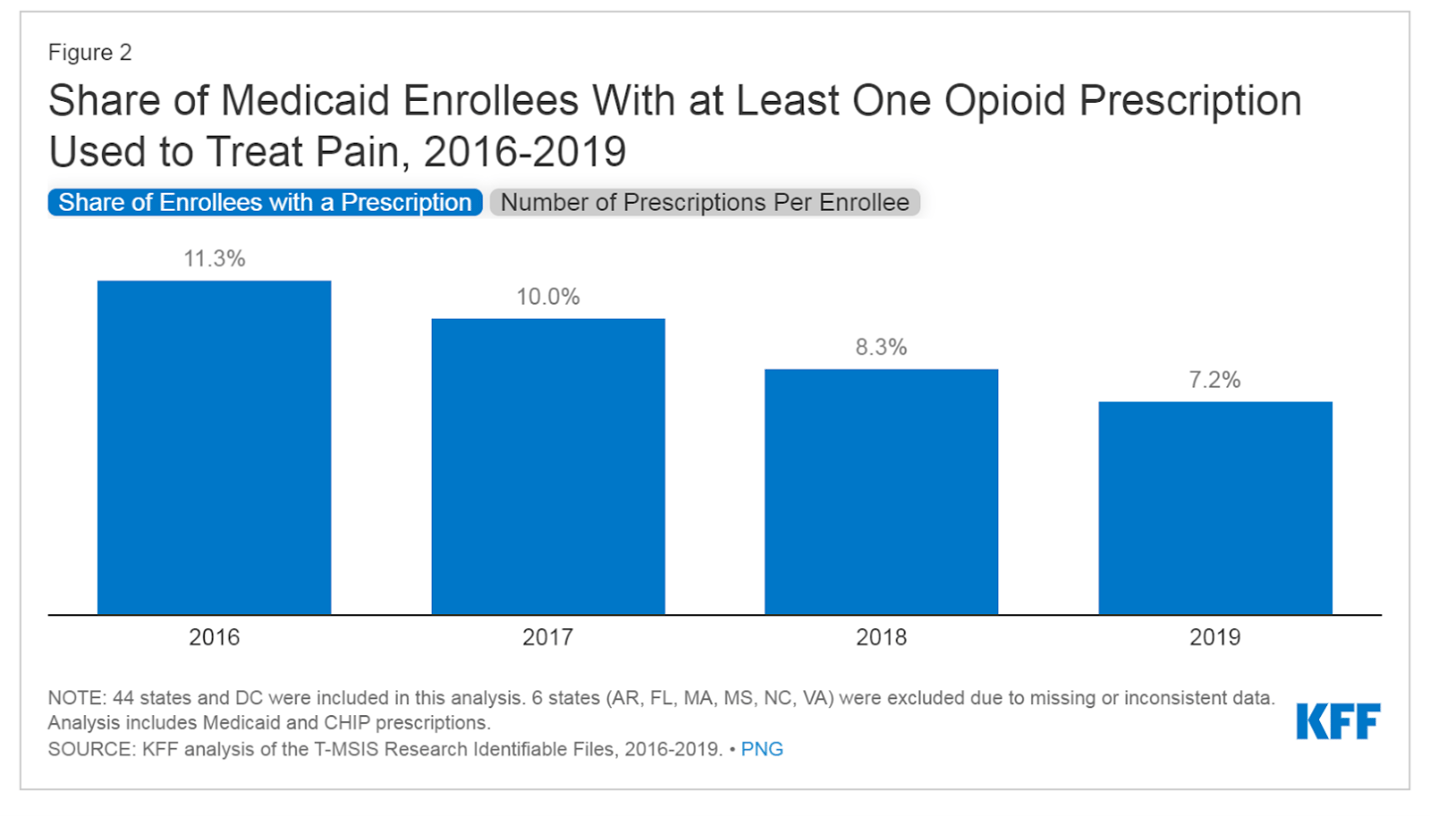

But while opioid access diminishes, access to other pain relief options is not increasing. A bill, the Non-Opioids Prevent Addiction in the Nation, or NOPAIN Act, was initiated in 2018 to pay for non-opioid treatments proven to reduce pain. It was approved in December of 2022 for post-surgical pain, but on July 13, 2023, CMS delayed implementation to 2025. Why? And in a country where innovation abounds, where pain drives the exorbitant health care costs, why are there so few solutions?

Pain education, pharma bias, and coverage policy are the three barriers to pain relief.

Organisms survive by avoiding situations that hurt. While amoebas withdraw (“Ouch!”), more complicated animals need to feel pain, withdraw, remember, weigh the danger, develop appropriate caution, and increase sensitivity to be warned more quickly in the future. As we can now see with brain MRIs responding in real-time, “pain” involves areas of sensation, memory, meaning, fear, and control.

IV opioids overwhelm this complex response to pain with intense rewards, as anyone with trauma appreciates. Because long-term elimination of the pain warning is a poor survival strategy, the reward receptors dull quickly to repeated exposure. Ongoing pain is maladaptive as well, so the body has many (heavily researched, some newly discovered) mechanisms to increase comfort: touch, pressure, temperature, and vibration nerves all override or reduce pain.

Movement itself, from tai chi to yoga to 10 minutes of cardio, changes the brain’s processing to reduce pain perception. Relaxation, sleep, and a diet with plenty of magnesium and antioxidants reduce acute and inflammatory pain.

Certainly, humans can learn to mitigate most kinds of pain with empowerment, options, and practice.

Why, then, do physicians rarely offer options for greater comfort?

In part because medical training hasn’t caught up to new knowledge. Purdue’s Oxycontin medical education in the ’90s espoused round-the-clock medicating to “stay ahead of pain.” The implication that pain-free was possibly dovetailed with well-intentioned doctors’ goals to reduce suffering. (I wore a “NO PAIN” pin on my white coat that I picked up at one of their noon lunches). This binary view of pain as off or on fits the medical mindset. Throughout the grueling med school selection process, there is one right answer to most multiple-choice questions. This monocular view of medicine, and the time devoted to pharmacology, still bias doctors toward pharmaceutical solutions.

Multiple choices and options are the right answer for pain management; silencing a survival system with a pill is the wrong goal. But understanding pain as a physiologic and neural interaction is recent, and the mix of biologic and neurotransmitter-based “biopsychosocial” pain relief is not simple. Surveys of familiarity with and barriers to recommending non-pharmacologic options often highlight a lack of physician education. After all, there is no magnesium lobby providing lunch education. Furthermore, the momentum from Purdue’s marketing – pain-free is the goal, and opioids are “the good stuff” – lingers in patients’ minds. The need for re-education applies to patients as well as physicians.

Even when doctors know and want to prescribe options or make a comfort plan, however, they don’t – because patients can’t afford them. Affordability is the policy barrier that crushes innovation for new pain relief options and muffles well-educated physicians from suggesting modalities. Given the costs of opioid use disorder, why don’t we address pain scientifically and economically? Because pain relief options aren’t covered by Medicare.

Medicare makes the decisions about coverage that insurance and Medicaid adopt. And in the Social Security Act, no Medicare payment “may be made under part A or part B for any expenses incurred for items or services … which constitute personal comfort items.”

Non-opioid options are the key to unlocking the neuroscience of pain control. Physicians don’t act on this knowledge because patients can’t pay. The industry doesn’t try to make new devices because they won’t be adopted without coverage. And the leftover legacy from marketing pain elimination with a pill prevents post-op patients from demanding post-surgical options.

Learn how to leave a public comment on the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services to increase access to non-opioids after surgery. The deadline for commentary is September 11.